🧬 Three Parents, One Baby: How Science Is Rewriting the Rules of Inheritance

Health & Science Feature – Varrock Street Journal

The Future of Family, Reimagined

What if a child could inherit the love, support, and genetic strength of not two, but three parents — and in doing so, be spared from a life-altering disease?

This isn’t science fiction. It’s the reality of three-person IVF, a technique once confined to theory and controversy — now producing healthy babies. This month, researchers confirmed that eight children have been born using DNA from three people: a biological mother, a biological father, and a female mitochondrial donor.

It’s a medical milestone. But it also opens deep questions about identity, genetics, and how far we’re willing to go to prevent suffering.

What Is Mitochondrial Disease, and Why Does It Matter?

Every cell in your body contains mitochondria, the tiny “power plants” that produce the energy cells need to function. Unlike the rest of your DNA, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) comes exclusively from your mother, and while it makes up less than 0.1% of your genome, it’s vital.

When this mtDNA contains harmful mutations, it can lead to mitochondrial diseases — rare but devastating disorders that affect the brain, heart, muscles, and more. These illnesses often show up in infancy or early childhood and can be fatal, with no known cure.

For families affected, it means an impossible choice: risk passing on a disease, or forgo biological children.

Here is a quick video explaining what a mitochondria does in case you need a refresher!

How Does Three-Person IVF Actually Work?

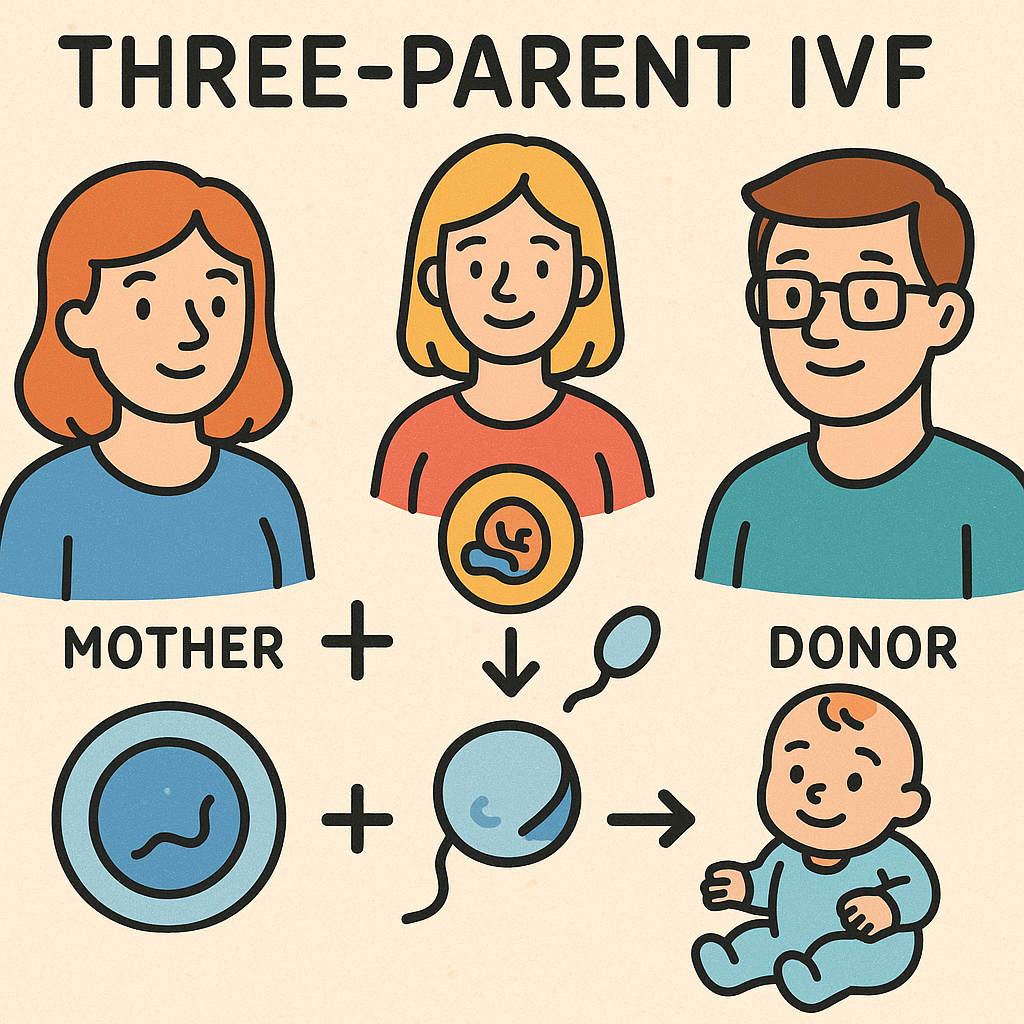

The goal is to create a baby that carries the nuclear DNA (which determines traits like eye color, personality, etc.) from the mother and father, but healthy mitochondrial DNA from a donor woman.

There are two main techniques:

1. Spindle Transfer (Used before fertilization)

- Doctors remove the nuclear DNA from the egg of the mother (with faulty mitochondria).

- This is inserted into a donor egg that has healthy mitochondria but has had its own nuclear DNA removed.

- The result: an egg with the mother’s genes and the donor’s mitochondria.

- That egg is then fertilized by the father’s sperm.

2. Pronuclear Transfer (Used after fertilization)

- Both the mother’s and donor’s eggs are fertilized by the father’s sperm.

- The pronuclei (genetic material) are removed from both.

- The mother’s pronuclei are placed into the donor’s zygote (fertilized egg with healthy mitochondria).

In both cases, the resulting embryo has:

- 99.9% of its DNA from the two parents

- 0.1% of its DNA — the mitochondria — from the donor

The child is not a genetic clone of three people. They won’t have traits from the donor — just her energy-producing cellular machinery.

Why This Matters

This is more than just an IVF upgrade. It’s a new paradigm in reproduction.

For couples with a known risk of mitochondrial disease, it means hope without heartbreak — the chance to have a biological child who won’t inherit a lethal condition. And while the number of births is small (so far only eight confirmed), the proof-of-concept is clear.

It also raises the possibility of treating — or preventing — a host of inherited mitochondrial conditions, from neuromuscular disorders to certain forms of epilepsy and heart disease.

Here is another great podcast if you're looking for more information on IVF!

Spotlight on Future Applications

- Expanding access: Currently approved only in a few countries (like the UK), this could grow into a global fertility option if shown to be safe long-term.

- Preventative medicine: Families with known mitochondrial mutations could someday be screened early and offered three-parent IVF as a first-line preventive measure.

- Broader gene therapies: This work also advances our understanding of germline gene editing — altering genes that will be passed to future generations.

But there are ethical considerations. Critics warn that this opens the door to designer babies, eugenics debates, or slippery-slope enhancements. Others argue it’s no different than an organ transplant — except on a microscopic scale.

Reflection Questions

- Should this type of genetic intervention be offered to all families at risk of inherited disease — or limited to rare cases?

- What rights (if any) should the mitochondrial donor have?

- Could this technology shift how we define parenthood?

📚 Sources

- The Guardian (2025). Eight healthy babies born after IVF using DNA from three people. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2025/jul/16/eight-healthy-babies-born-after-ivf-using-dna-from-three-people

- Scientific American (2025). Three-Person Mitochondrial IVF Leads to Eight Healthy Births. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/three-person-mitochondrial-ivf-leads-to-eight-healthy-births/