🦠 Invisible Invaders: What’s Lurking in the Water This Summer?

Swimming Summer Series | Week 3 – Varrock Street Journal

What is happening everyone!? Welcome back for another weekly edition of the Varrock Street Journal!

As you splash into the final weeks of summer, everything might look picture-perfect — the sun is out, the water is cool, and there’s nothing like a long swim to beat the heat. But there’s more beneath the surface than what meets the eye. Some of the biggest health threats this season are invisible pathogens floating in lakes, pools, rivers, and even hot tubs.

This week, we’re turning our attention to waterborne illnesses — the less dramatic but incredibly common side of aquatic medical risks. From Cryptosporidium outbreaks in swimming pools to E. coli at lakeside beaches, it’s time to talk about what really causes that “pool flu” — and how to protect yourself, your kids, and your community.

What Are Waterborne Illnesses and Where Do They Come From?

Waterborne illnesses are caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites that spread through contaminated water. You don’t need to swallow a lot — sometimes a single mouthful is enough. Public pools, splash pads, and freshwater lakes are frequent sources, especially when sanitation is poor or people swim while sick.

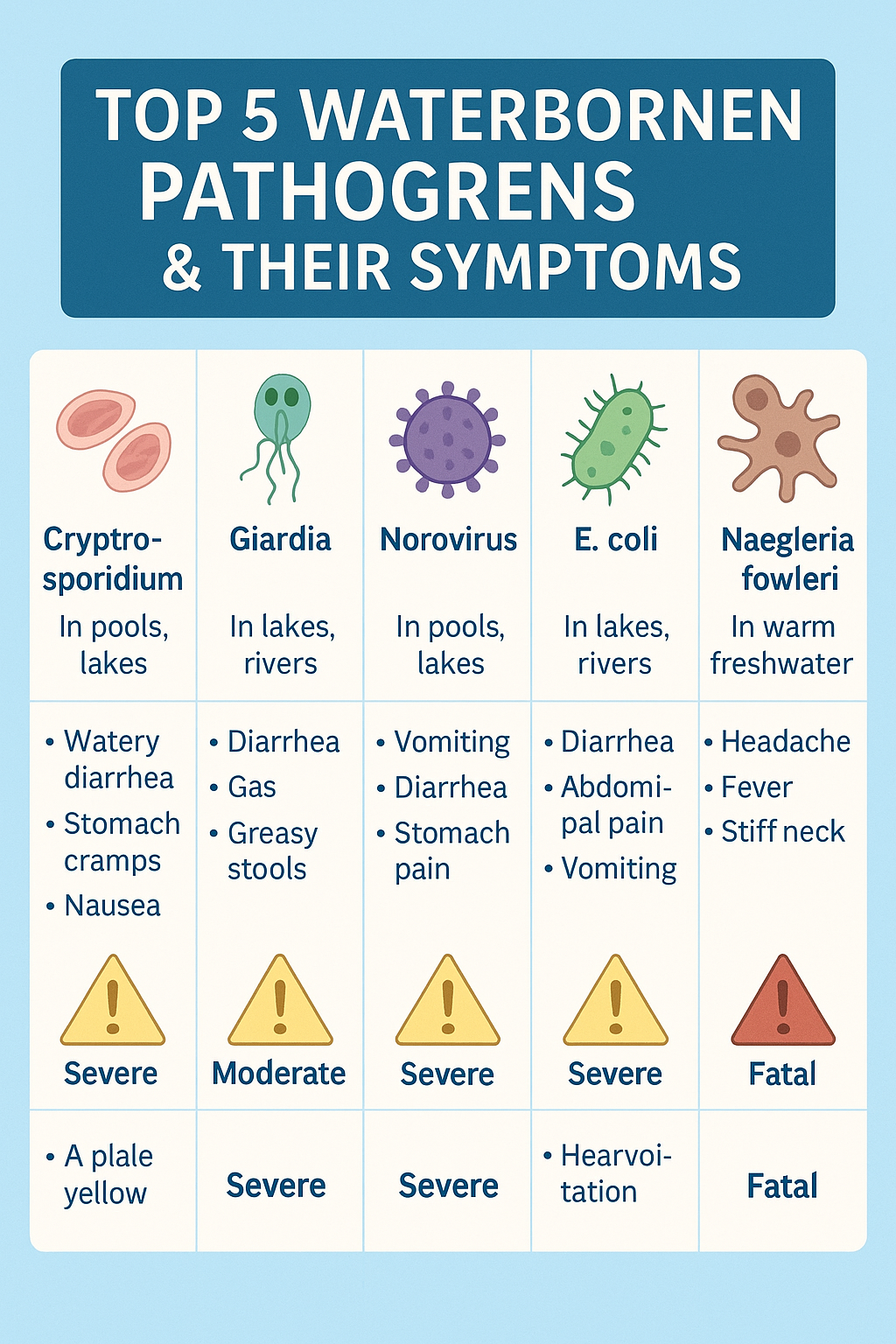

Common pathogens include:

- Cryptosporidium: Highly resistant to chlorine; causes explosive diarrhea

- Giardia lamblia: Parasite found in natural water, especially after heavy rains

- Norovirus: Extremely contagious; causes vomiting and diarrhea

- E. coli & Shigella: Fecal bacteria from humans or animals; common in lakes

- Naegleria fowleri ("brain-eating amoeba"): Rare but deadly; enters via the nose in warm freshwater

These bugs can live in chlorinated pools, hot tubs, and even natural springs. Once exposed, symptoms usually start within a few hours to a few days and include:

- Diarrhea

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

- Stomach cramps

- Dehydration (especially in children and older adults)

Treatment and Public Health Response

Most waterborne illnesses are self-limiting, meaning they go away on their own within 1–2 weeks. Treatment focuses on hydration, electrolyte replacement, and symptom management. However:

- Infants, elderly, and immunocompromised people may need hospitalization

- Certain infections (like Shigella or Naegleria) may require antibiotics or antiparasitic drugs

- Public health authorities often track outbreaks and can shut down facilities

If you've been sick, don’t swim for at least 2 weeks after diarrhea resolves — especially with Crypto, which is notoriously hard to kill with normal chlorination.

Prevention: What You Can Do

Protecting yourself and others from waterborne illness doesn’t mean avoiding the pool — just being smart:

- Shower before and after swimming

- Don’t swim if you’ve had diarrhea recently

- Avoid swallowing water — teach kids this early

- Watch for pool closure signs — they’re based on real data

- Use nose clips in warm lakes (especially in southern U.S.)

- Test private pools or hot tubs regularly

Why This Matters

Each year in the U.S., tens of thousands of people get sick from recreational water exposure, and many outbreaks go unreported. A 2019 CDC study showed that Crypto caused over half of all swimming-related illness outbreaks in the prior decade. In a post-pandemic world where cleanliness is on everyone's mind, improving public pool hygiene and swimmer behavior could prevent countless cases.

Here is a podcast discussing various waterborne infectious diseases that are occurring in the United States due to ongoing tropical storms!

Spotlight on Future Applications

Public health experts are pushing for:

- Real-time pool monitoring systems to detect chlorine and pH fluctuations

- Pathogen-detecting smart sensors in high-traffic waterparks

- National campaigns to educate swimmers about crypto and giardia

- Open-source reporting platforms to crowdsource outbreak warnings

Science is also exploring bacterial-resistant filtration systems and UV sterilization tech that works alongside traditional chlorination.

Reflection Questions

- Should public pools enforce a “no swim” period after illness — or is that too difficult to monitor?

- How can we better educate children about pool hygiene without scaring them?

- What role should private pool owners play in community-level water safety?

📚 Sources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Recreational Water Illnesses.

- Hlavsa, M. C. et al. (2019). Outbreaks of Illness Associated With Recreational Water — United States, 2000–2019. MMWR.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Safe Recreational Water Environments.

- Mayo Clinic. (2022). Giardia Infection and Cryptosporidiosis Overview.